The story about Liukas Hackathon

17 December 2024

Optimizing transport kilometres, working hours, and nutrient deliveries with integrated solution – The story of LiukasHackathon

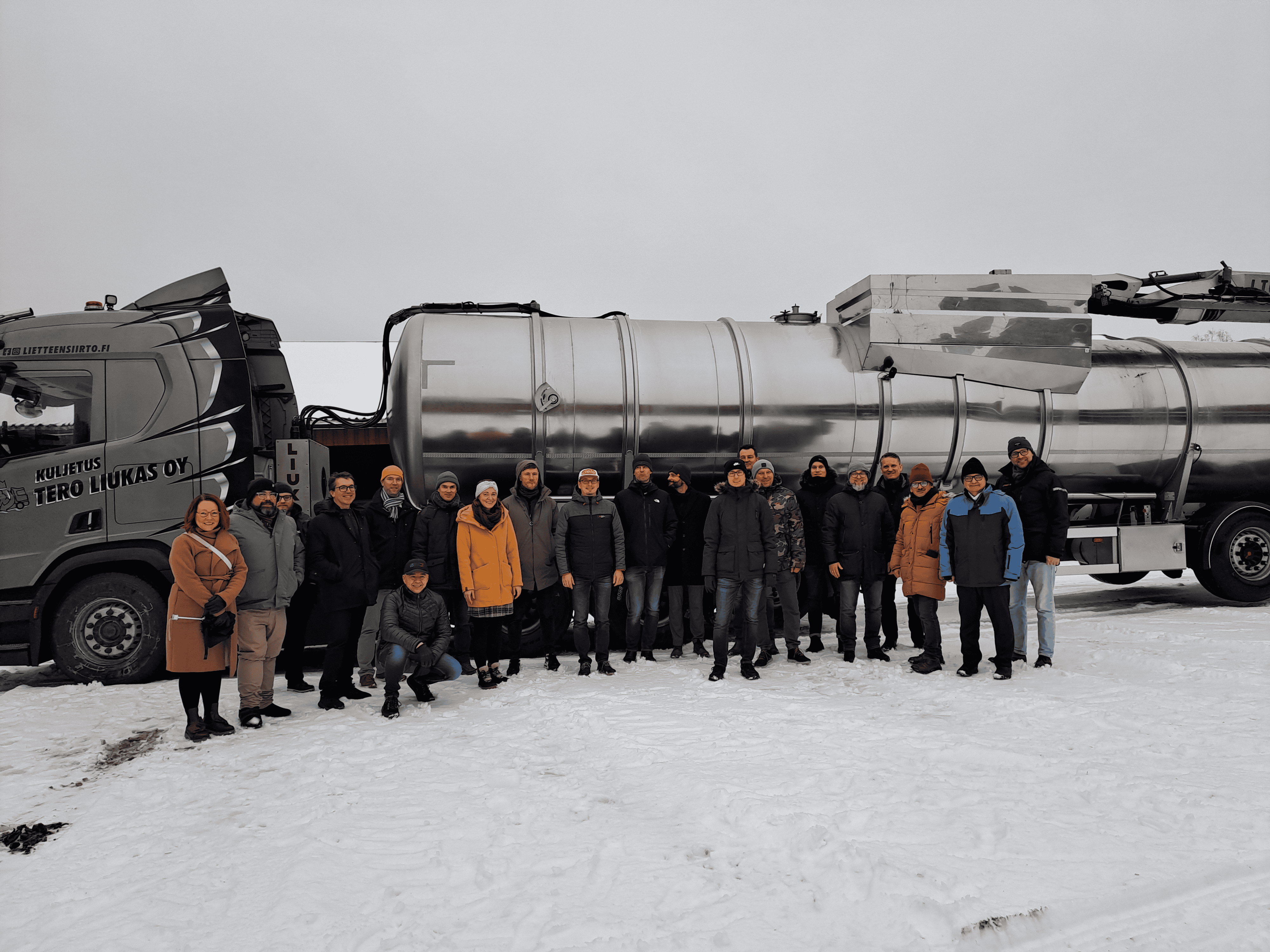

Organised by Jamk University of Applied Sciences with Kuljetus Tero Liukas Oy and Finnish Biocycle and Biogas Association, the international LiukasHackathon innovation competition sought a smart logistics solution for the transport of recycled nutrients. On the final hackathon day, 26.11.2024, three winners with complementing solutions were named in the competition – Aiseemo and Freight Automation by Hogs from Poland and Waybiller from Estonia. Proposals for the combined solution will be piloted in co-operation with Kuljetus Tero Liukas Oy in 2025. The Finnish-Polish-Estonian partnership plans to deliver a solution for the growing needs of the biogas and recycled fertilizer production logistics.

In this article, the coordinator of the LiukasHackathon process, Anna Aalto from Jamk University of Applied Sciences, explores the lessons learned from the point of view of the organising team.

How was your second BioBoosters hackathon organising experience different from the first one? Did you learn something new?

In ValioHackathon last year, we were working with a large, globally operating enterprise that has a well-known and valued brand. In LiukasHackathon, we worked with a SME that is operating regionally in Southern Finland in a very specific logistics niche. This obviously creates a different starting point for the open call marketing campaign. Nevertheless, we were able to attract 15 applicants which was not a major decrease from the 18 applicants in ValioHackathon. Based on my personal analysis, the success factors were tangible co-operation offer for the winning teams and effective active scouting (by our own team and the BioBoosters network). Furthermore, the co-operation with Finnish Biocycle and Biogas Association and the growing brand-recognition of ‘BioBoosters’ supported the communication campaign success.

In practice, the main difference was that when working with Valio, there was a team of 6-8 experts involved in each step of the process while the team of Kuljetus Tero Liukas Oy was 1-3 persons. A smaller team is flexible and quick to make adjustments and shifts when getting new signals or lessons. With Valio, the priorities were more fixed throughout the process. As one may imagine, there are pros and cons with both options.

Greater level of international participation also provided a few practical lessons, e.g. on the management of travel cost claims as well as on hospitality and hosting practices. Still, the main observation was that the completely international finalist group did not much affect the process or management of the hackathon flow. It was great have a big group of international specialists connecting at our rural Bioeconomy Campus situated in the village of Tarvaala in Saarijärvi, Northern Central Finland.

What kind of help you got from the international partnership in organizing a BioBoosters hackathon? Has the co-operation in the partnership developed compared to the first round?

It seems that the international attraction to the hackathons is growing since last autumn. LiukasHackathon was exceptionally international, largely thanks to the well-functioning active scouting co-operation for teams and mentors. The open call for LiukasHackathon attracted 15 applicants from seven countries. Nine international teams applied exceeding our expectations greatly. Even though we knew that the challenge was common in many Nordic countries, we were not initially sure that there would be interest to join the hackathon featuring a challenge from a nationally (or regionally) operating SME.

After team selection, we started out with seven teams from five countries – Finland, Sweden, Poland, Estonia and Spain. At the Kick-off stage, the Finnish team dropped out and Swedish team, Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE), opted to take the mentoring role in the process. Thus, at the Hackathon days, all the finalists were international. All of the teams travelled onsite, which showcases their commitment to the process. Furthermore, we got four international mentors via the BioBoosters partnership, namely via Pro Civis (Poland), Pärnu County Development Center (Estonia) and Sunrise Tech Park (Lithuania). With the addition of RISE specialists, there were quite equal amount of international and national mentors involved in the process.

What lessons would you like to share with other Hackathon organizers?

Based on our experiences, BioBoosters hackathons process works with large enterprises and SMEs. It works with challenges of lower and higher TRL levels. It works nationally and internationally. It works with complex challenges and with simple ones. However, there are certain key aspects that the organiser should address when planning the process with the challenge provider.

First, there needs to be a tangible business and/or co-operation offer for the solution provider. Whether a large enterprise or SME, the challenge provider should be able to provide a practical offer for the winning team. Therefore, it is necessary that the challenge is formed based on a real need that is prioritised by the challenge provider company. In LiukasHackathon, we were able to make a convincing offer for the potential solution providers as Kuljetus Tero Liukas Oy had a R&D grant in the pipeline for implementing the co-operation with the winning team(s). This made it possible to have a successful open call and attract teams to the challenge. Also, the launching the co-operation after the hackathon is likely to be more effective.

Secondly, real-world challenges are often complex, and the practical limitations need to be addressed clearly with the teams. This may require committed engagement and extensive dialogue with the teams already during the development phase to guide the teams in making applicable solution proposals. In many cases, there are various sustainability or business trade-offs between different solution paths. Focusing on a single aspect of a challenge can result in limited learning opportunities in the open innovation process and partial optimisation. In other words, limiting the scope of the challenge too much may lead to a solution that would not offer a holistic, integrated approach to the circular transition.

Of course, the process is easier with a more focused challenge – communication messages, target groups, offers and evaluation are clearer. It is easier to manage the whole process flow, to engage the participants, and to communicate with them. This is important to understand and also to communicate with the challenge provider when preparing the challenge definition. It is necessary to make the challenge provider aware that if the challenge is complicated, they will most likely need to engage with the teams more during the development phase.

In the case of LiukasHackathon, there were several needs related to digitisation and tackling this complexity of demands and evaluation criteria required quite a lot of effort from challenge provider, teams and mentors during the process. The question arises… Should we have simplified the call for solutions by focusing on only the real-time measurement of the sludge tank capacities and leaving out the other digitisation needs? I have considered this aspect a lot.

Focusing on one digitisation need would have simplified the work of the teams, mentors, and, of course, the organisers. We may have identified more solutions to tackle one key issue. However, if we had done it, we would have left out at least one of the teams that actually ended up winning, e.g. with a solution on digitalisation of freight documentation and billing process. We would have also limited the open innovation dialogue on nutrient data flow and management. This co-learning may prove to be even more impactful in the longer term. Luckily, our challenge provider team was very engaged in the co-working with the teams during the development phase in Howspace. Teams were very happy about this interaction as was evident e.g. from the team interviews and feedback survey.

All in all, complexity creates uncertainty and pushes us into the discomfort zone. Nevertheless, it can lead to more impactful results and greater learning on the challenge. I would advise not to be afraid of the complexity and to let the need of the challenge provider guide the process design and challenge definition. As the guide of the open innovation process, it is still advisable to communicate these implications clearly to the challenge provider. Easier or more convenient is not always better; still when taking the harder road, we need to make sure the challenge provider is willing to put in the necessary working time to guide the teams to making impactful and applicable solution proposals.

Will we see more BioBoosters hackathons in your region after the project?

Yes, BioBoosters by Jamk business accelerator has organised or co-organised already 29 hackathons, and the next one is just around the corner. In January, we will launch the open call for a hackathon with YIT, a construction and development company. We have actually worked with YIT before. In 2022, YITHackathon was organised with a challenge to find new ecological materials that effectively bind dust particles during the surface treatment of gravel roads or form a binding layer on the surface of the road. Winning solution featured utilization of forest industry side streams in dust binding replacing the typically used salts. Now, YIT has a new challenge for us, and we are happy to be able to launch an international call for solutions alongside with the five BioBoosters hackathon co-funded by the Interreg BSR program.

Furthermore, R&D projects of Jamk University of Applied Sciences are capitalizing on the hackathon process expertise, and e.g. ‘Finnish Future Farm’ project is going to deliver three hackathons with calls for digitalization solutions in agrifood system in 2025-2026. Whether organised via service sales or R&D projects, we anticipate to continue organising BioBoosters hackathons steadily in the coming years.

Interactive map showing pilot locations. Use the arrow keys to move the map view and the zoom controls to zoom in or out. Press the Tab key to navigate between markers. Press Enter or click a marker to view pilot project details.