Working on a project - interview Dr. hab. Justyna Siemionow, Associate Professor at the University of Gdańsk (UG)

07 April 2025

Dr. hab. Justyna Siemionow, Associate Professor at the University of Gdańsk (UG), from the Institute of Pedagogy at the Faculty of Social Sciences, talks to M.A. Magdalena Nieczuja-Goniszewska, UG Press Officer.

– We arranged this interview in connection with the completion of the ongoing Mobile Hospital – Digital Counseling Environment for Children and Families project. Could you tell us how it all started?

– We began the project in August 2023. It stemmed from my Finnish contacts from many, many years ago. I’ve been collaborating with Turku University of Applied Sciences (TUAS) practically since 2016. I visited TUAS several times as part of the Erasmus+ program, gave lectures, held meetings with faculty, and talked to various researchers. One day, I was asked whether our university would like to join the project as a partner. I didn’t know the people who would be involved at all, but after a few conversations, we concluded that it was possible. The application for funding was preceded by many hours of online meetings. I’d like to add that aside from us and Finland, there’s also a partner from Sweden – Karolinska University Hospital. Preparing the application was quite complicated due to the different working styles and procedures of the partners. But we succeeded, and it turned out we received funding, which made me very happy. I must emphasize that our team at the University of Gdańsk has been doing a lot and putting in a great effort. The project leader has praised us repeatedly – not only are we completing our assigned tasks, but we’re also doing much more. Our main responsibility is evaluating the application, but we were also involved in content development.

– Could you remind us what the project is about?

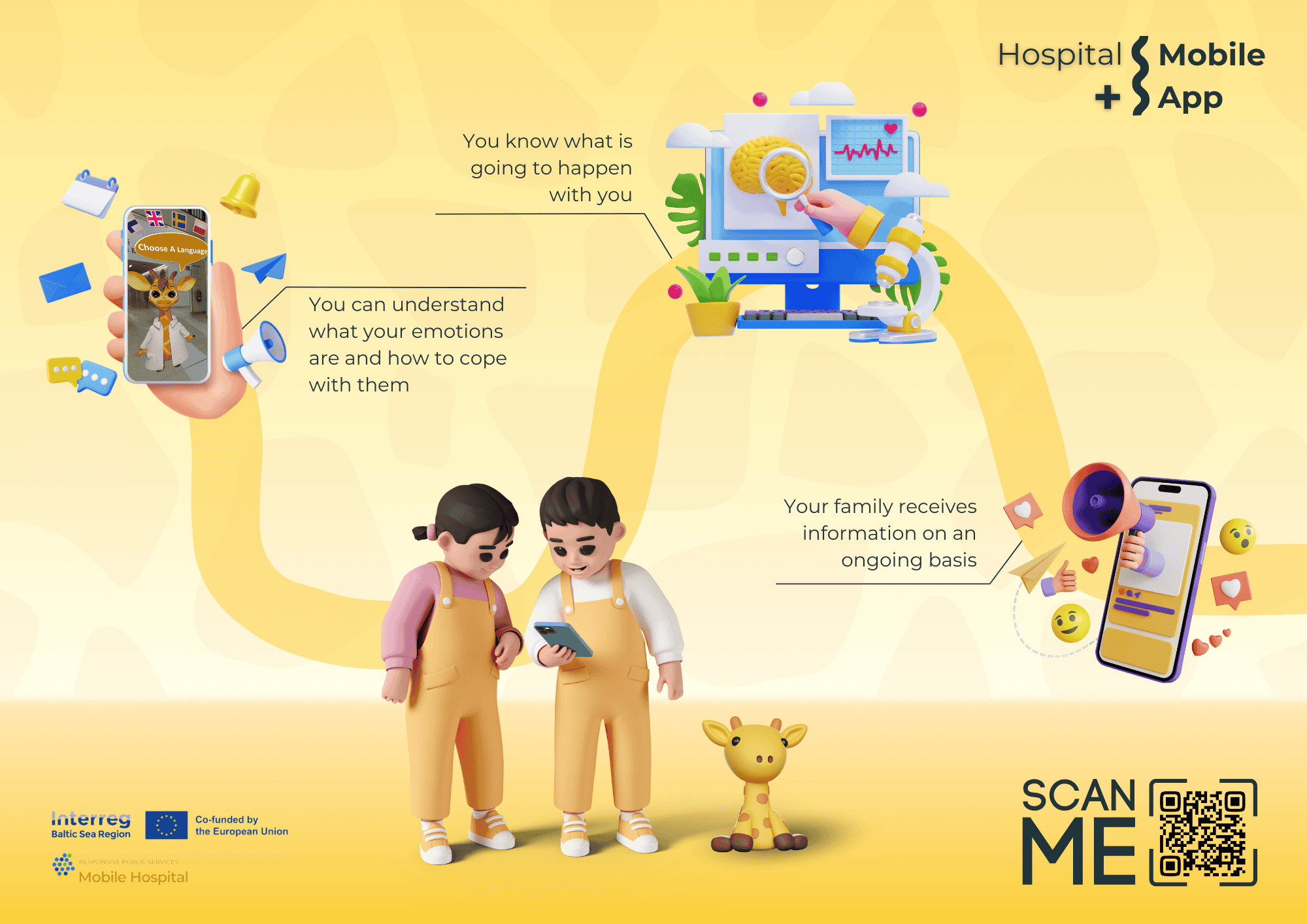

– The project is fundamentally very interesting in its premise, even if the concept itself is no longer groundbreaking, as similar apps already exist. Our app, which can be used on a phone or another device, is designed to help children and their parents/caregivers become familiar with hospital-related topics, medical procedures, and treatment-related issues. As I mentioned, there are already quite a few such applications on the market, but ours stands out in that it is highly universal – it can be used by both young children and older ones, as well as by their parents. Our team’s role was to show how children at different ages perceive, understand, think, what kind of messages they comprehend, and how they experience the world around them. This application was developed with all those developmental aspects in mind.

The issues related to nursing and working with healthcare staff were handled by our Finnish and Swedish partners. We don’t train nurses at our university, although I think in the future we could partner with the Medical University of Gdańsk (GUMed) within the Fahrenheit Universities framework. Anyway, the medical staff on their side worked with scientists to determine what should be included and what to focus on when designing the app. Since there are already many similar applications out there, ours had to stand out.

That’s why we designed it so the child can safely use the app independently. However, since we – the UG team – believe that hospital contact is also very stressful for parents, we emphasized the importance of helping parents manage their emotions and share them with their child. If parents can cope with their own emotions, they are better able to help their child – a bit like the airplane rule: put on your own oxygen mask first before helping others. That’s why the app encourages parents to go through it together with their child. It’s designed so that you can start at any moment and stop at any time. Animated characters guide the child through the hospital and explain things in an accessible way, helping to familiarize them with the hospital environment.

You could say it’s like a 3D game. The child can click, choose whether to view one image or another. Smiling animated characters, generated by artificial intelligence, encourage exploration of various areas of the hospital. Selecting appropriate characters took a long time and was preceded by lengthy discussions. Right now, we’re preparing to host the app on the University of Gdańsk’s server and begin testing.

– Why on the university server instead of, say, Google Play?

– I believe hosting the app on our server will inspire more trust among parents. It will also be harder to hack and insert inappropriate content. We want parents and caregivers to feel completely safe using the app.

– You mentioned that working in such an international project team, where different work cultures clash, isn’t easy. Could you say more about that? It’s not something people talk about very often.

– It’s a collision of different work models. We often juggle multiple tasks at once, and sometimes we’re overloaded. If needed, we work in our free time, at night, on weekends, to finish something or prepare for lectures – that’s just how it is, and we’re used to it. Meanwhile, the Scandinavians – both Swedes and Finns – work strictly Monday to Friday. You get done what you get done. I love their saying: you did the best you could. Even sending emails on weekends is considered rude. They don’t read them, but if they do on Monday, they see it as pressure and poor etiquette. They value their time greatly.

That’s something I’d really like to learn from our partners – and I admit I’m making progress. The difference in work models was noticeable, but I think it’s fascinating to learn from each other. Sometimes I look at it with envy, and other times I think it’s probably impossible to work like that in our context. But the most important thing is that despite the differences, we’ve managed to complete the project harmoniously – the app is ready. We’re now approaching the final stages.

– Were differences in working styles the only challenges your team faced during the project?

– No. Finland, Sweden, and Poland also differ in terms of hospital care models. Though, I must say, there’s nothing for us to be ashamed of. Hospitals in Poland, especially those for young patients, are colorful, well-equipped, and child- and parent-friendly. However, my colleague involved in the project, Dr. Patrycja Brudzińska, and I decided not to include photos of Polish hospitals in the project. That’s partly because we were in a period of high illness rates among children – we couldn’t enter wards to take pictures.

The project has different implementation stages, and each task has a set timeline.

– Are these pictures of the entire hospital, various departments, or did you focus only on pediatric wards?

– Only pediatric wards. They tend to be more colorful and different. Besides photos and animations, each team conducted research on the medical aspects – looking into the most common illnesses, typical hospital cases, and the everyday challenges of pediatric wards. It turned out these issues are quite similar across all three countries.

The app’s pathways are tailored to specific illnesses or medical situations – for instance, if a child has diabetes, a broken leg, is awaiting surgery, or has pneumonia, they can click on that path to learn what might happen, who they might meet in the hospital, etc. It’s all described in an accessible way, aligned with how young children think and perceive – something we paid close attention to on our end.

It’s a very intuitive app, and we believe that children – who are increasingly familiar with virtual environments – will be able to navigate it safely. We’ve invited a group of children and their parents to test the app on April 12, 2025. We’re really looking forward to it!

How large is the group and who are these children? What is their age?

– There will be 15 participants. Due to current legal requirements, we also had to invite parents, which was actually the biggest challenge. But we managed to invite them. The children are between 5 and 8 years old – the idea was to involve younger children. The app can certainly be used by older kids and even teenagers, but younger children usually find such situations more difficult and need adult support. During the workshop, we want not only to observe how the child reacts to the app, but also to examine the parent-child interaction while using it. It’s important to us that parents also feel this is a tool for them – and something worth recommending. I’d also like to emphasize the role of the POZYTYWNI.PL Foundation, which is collaborating with us and making it possible to test the app.

– As you mentioned earlier, parents often fear the illness and its consequences for their child more than the young patients themselves, who may not fully grasp the situation.

– Exactly. And that’s why using the app together is so important – both in terms of online safety and to be able to explain things when questions arise. The app is designed to support parent-child interaction. It enables emotional sharing, which is crucial for a child to see that parents also experience emotions like fear but know how to manage them. Both Dr. Patrycja Brudzińska and I have experience working with children and parents, and I’m convinced that this app can also help calm and emotionally stabilize the parents – and that, in turn, will benefit the child.

It’s also a great support tool for doctors and nurses, because parents’ stress and anxiety can sometimes hinder or “block” the recovery process. Additionally, the so-called “white coat” can cause anxiety in children, even though medical staff today often wear colorful uniforms – that syndrome still persists.

– Did you conduct research related to this as part of the project?

– Yes, we did, and we also plan to write a paper about using this kind of app not only in healthcare but also in children’s education. Previously, implementation projects didn’t require academic publications. However, one of our Swedish colleagues told us that Erasmus+ funding now expects a research component to be included.

This is actually good news for us – for the university – because institutions that aren’t research-focused will look for partners like the University of Gdańsk to provide that academic dimension. On that note, our university is very well-regarded among European institutions, making us a strong partner with excellent staff and research potential.

Back to our research – one thing we found is that parents often struggle with specialized medical vocabulary or short, technical communications from doctors. Doctors in Poland often have many patients and don’t always have as much time for individual conversations as they might like. This is where we see a difference compared to Scandinavia. There, a parent can sit in a designated room, have tea or coffee, and talk at length with a doctor. Email communication with medical staff is also common.

So we started thinking during the project: how can we help improve communication between doctors and parents? Sure, you can Google things, but that’s not enough for a parent. So that’s one idea for future development. Doctors and nurses are key figures in the healing process – and the so-called support staff also play a vital role in pediatric wards.

In Poland, doctors are doing their best. I spoke with doctors in Malbork, where there’s a small pediatric ward, and we established a partnership with them before flu season hit. The doctors there said they’re aware of such apps and receive training on them – it’s not something entirely new for Polish healthcare – but they don’t really use them yet.

So we’re hoping this pilot will be successful and that the app will be a fun experience for kids, while also supporting parents and healthcare professionals.

– What’s next for the app – we know when it will be tested, how it was developed, and that it won’t be downloadable via platforms like Google Play.

– After the testing phase and making the app available through the university’s website, we’ll begin promoting it. This has been a thorough, well-thought-out, and carefully executed project, and we believe it can bring real benefits. We were especially focused on making sure the app stood out thanks to its deep, substantive quality – which the University of Gdańsk contributed.

Of course, we’re not delivering psychology lectures for young children, but the psychological and pedagogical foundations are clearly visible – and our work was dedicated to that. We’ll also be promoting the app among students, especially those training to work in preschools or in special education. The app can be very helpful even for older children with intellectual disabilities, to help them understand what’s happening in a hospital setting and why.

The app will be completely free to download. The project was funded by the European Union, and it should serve the public.

We still have several months of intensive promotional work ahead, and we’ll be fine-tuning the app “until the last minute.” This project was so intense that, on the one hand, I’m glad the implementation phase is ending – but on the other hand, I’ve already been working on another project with the same university in Turku. It was about an app for social workers, but unfortunately, it was submitted during a time when there were many applications and fewer funds – likely due to the global situation – and it didn’t receive funding.

Still, that experience with Turku University of Applied Sciences was valuable, and I hope the project will be revised and resubmitted – we’re still considered part of it.

I’m convinced that more joint projects with Finland and Sweden are ahead of us. This project has been a wonderful professional and personal experience for our team – myself, Dr. Patrycja Brudzińska, and Dr. Katarzyna Wajszczyk, who joined the project in March 2025. We’ve learned a lot from our partners – and they’ve also learned from us.

Teamwork and project-based collaboration are a natural fit for researchers and educators, because we can share those experiences with our students.

And I’d like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Patrycja Brudzińska and Dr. Katarzyna Wajszczyk for their collaboration on this project.

– Thank you for the conversation.

The article was published on the University of Gdańsk website (www.ug.edu.pl) on March 31, 2025.