Building and renovating with ecolabels: tools to reduce environmental pollution through Green Public Procurement

07 October 2023

The potential for sustainable public procurement is particularly high in the construction sector due to its high emissions and large contracts. So far, most countries are estimated to use Green Public Procurement (GPP) for less than 5 % of their contracts [1, 2] .

Among the front runners Denmark and Sweden have increased the average share of GPP relative to total public procurement to up to 15 % and 10 % respectively. Welcome ambitious goals to raise this share to 25 %, 30 % or even 100 % have recently been set by policy makers in Poland, Estonia and Lithuania [3]. In general, in the EU-27, regional and local governments tend to adopt GPP more often than central governments or EU contracting authorities, indicating a high motivation for GPP despite limited resources [4].

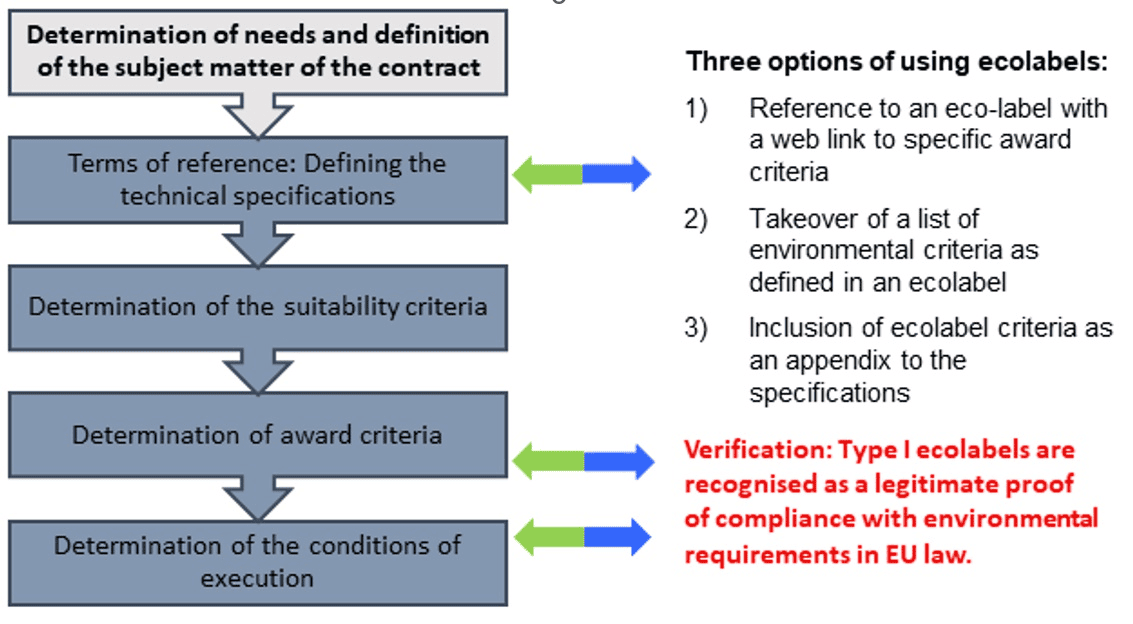

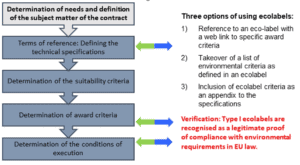

GPP is well suited to achieving the aim of replacing hazardous chemicals with safer alternatives. When reliable, up-to-date environmental and chemical criteria for goods or services are missing, the administrative burden for both the competent authorities in defining criteria and for the companies concerned in supplying the relevant verifications is seen as one of the main barriers to the implementation of GPP. A tried and tested solution often applied by municipalities is to use the criteria developed within the framework of ecolabels (see figure below) in GPP. Ecolabel criteria are based on scientifically validated information and are updated in line with technological progress. From the outset, ecolabels address those stages of the product life cycle where relevant environmental benefits can be achieved.

As shown in the attached figure ecolabels can be used at different stages of Green Public Procurement. (see full scheme below)

By purchasing ecolabelled products Green Public Procurement can:

- avoid toxic substances, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss and waste of resources,

- create first lead markets for products with environmental benefits,

- contribute to cost reductions through economies of scale and learning effects and

- strengthen the acceptance of new types of goods by private customers.

For example, the successful use of climate-friendly, recycled building materials in public construction projects increases the acceptance of these products by the general public [5] .

NonHazCity 3 advocates for the introduction of chemical criteria in public procurement for buildings, renovations, construction services and materials. Where such criteria have not yet been defined at EU level or national level, we recommend the use of Type I ecolabels as defined in ISO 14024 [6] to define rules at the municipal level. These are certified environmental labels for which the responsibility for awarding the label lies with a body that is independent of the label holder. They identify particularly environmentally compatible products within a product group. Ecolabels according to Type I of ISO 14024 are, for example, the Nordic Swan, the EU Ecolabel and the Blue Angel. The underlying criteria are usually very well suited as a basis for tenders, especially because they mostly address environmental impacts throughout the entire life cycle and contain ambitious requirements. This guarantees a high level of environmental relief or protection.

NonHazCity 3 recommends referring to the following ecolabels, where possible. The Nordic Swan has developed criteria for a wide range of building products from adhesives to wooden floors, and for types of new buildings from schools to family homes as well as for the renovation of existing buildings. These are accessible for free download at: https://www.svanen.se/en/how-to-apply/criteria-application/. Products available on the market and buildings that have received the Nordic Swan are listed at: https://www.svanen.se/en/categories/house-and-building/. By visiting the product database, it is easy to see, whether products that meet the ecolabel criteria are readily obtainable on the market or not.

Nordic Swan ecolabel

The EU Ecolabel

The EU Ecolabel criteria for instance for indoor and outdoor paints and for various floor coverings can be consulted free of charge at https://eu-ecolabel.de/en/for-companies/product-groups. Products with the EU Ecolabel on the market can be found in the Nordic Swan database (link above). The product search feature would be a helpful addition to the EU Ecolabel Database too. The Blue Angel criteria for construction products as well as the corresponding Blue Angel products can be found at https://www.blauer-engel.de/en/certification/basic-award-criteria#. In many cases the Nordic Swan and the Blue Angel cover the same products group. If, for example, the Nordic Swan is required as an award criterion in GPP, the EU Ecolabel and the Blue Angel can be cited as equivalent, where available. Although the criteria may differ in detail, the level of ambition to achieve a toxic-free environment is high for all three ecolabels.

Blue Angel Ecolabel Logo

In a recent study of chemical requirements in Swedish municipal green public procurement, the complexity of chemical risks, respective knowledge gaps and lack of follow-up compliance of criteria were identified as challenges for municipalities [7]. NonHazCity 3 encourages municipalities to make use of ecolabels to address these challenges. The monitoring of criteria compliance is taken care by the Type I ecolabelling organisations, including third party verification and market surveillance. In this way ecolabels can help to realise the full potential of GPP in reducing hazardous chemicals.

As a next step NonHazCity 3 encourages a move from procuring individual building products with ecolabels to procuring a complete ecolabelled refurbishment or building (see Nordic Swan award criteria). The picture above (photo by Elisa Keto) shows a kindergarten commissioned by the City of Helsinki to be built to meet the Nordic Ecolabelling certification criteria. In the ecolabelled building ecolabelled materials and products have been used as far as possible.

[2] https://www.switchtogreen.eu/eu-green-public-procurement/

[4] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123710

[5]https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.572799.de/diw_econ_bull_2017-49-2.pdf

[6] https://www.iso.org/standard/72458.html

[7] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126701

Authors: Outi Ilvonen (German Environment Agency), Ingrida Bremere (BEF Latvia), Jolita Kruopiene (Kaunas University of Technology), Protic (Kiwii) Siobhan (BEF Germany). Images from: Elisa Keto (City of Helsinki)