The ownership and responsibilities of the multi-apartment buildings in the BSR vary a lot, creating different challenges and need for support

30 May 2023

In the EU, there is a huge energy efficiency (EE) potential in the residential multi-apartment building stock. Buildings are the single largest energy consumer in Europe. Heating, cooling, and domestic hot water account for 80% of the energy that we, citizens, consume. Buildings are therefore responsible for approximately 40% of EU energy consumption and 36% of the energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.

At present, about 35% of the EU’s buildings are over 50 years old and almost 75% of the building stock is energy inefficient. At the same time, only about 1% of the building stock is renovated each year.

Project RenoWave (financed by Interreg Baltic Sea Region 2021-2027) focuses on a special target group – it aims to support home-owned multiapartment buildings (HOMABs) in their way towards energy-efficient renovations. HOMAB is typically not as professionally managed as buildings owned by public organisations or private companies. HOMABs often lack the knowledge on energy efficiency that public and private organisations have access to. HOMABs usually have some legal form that lays down the rules and process of decision-making among all residents living in the building. RenoWave addresses this challenge by developing an extended one stop shop OSS-model, designed to meet the needs of HOMABs.

The project has mapped the HOMABs situation in its partner countries and identified surprisingly different situations regarding the ownership and responsibilities of HOMABs.

The project’s starting point was that the countries have similar conditions and challenges regarding HOMABs. However, the mapping shows significant differences that must be considered when designing the support.

The mapping was done based on the partners’ own knowledge. It has not been possible to find any report that presents the situation and conditions of HOMABs in the BSR area. The statistic for Poland is based on rough estimations since statistics have not been found. A common understanding of the situation is also challenged by language barriers, with different terms for legal forms and building types. To avoid misunderstanding and to reach a deeper understanding of different situations in different countries, a table for definitions and translations has been added to this article.

Key findings:

Ownership of multi-apartment buildings

The mapping has identified two groups of countries that share more or less similar conditions, but the differences between these two groups are considerable.

One group contains Sweden, Finland, Germany, and Poland with a mix of multi-apartment buildings owned by private companies, public organizations, and HOMABs. In Sweden approximately 40 % of the multi-apartment buildings are home owned, in Finland 52 %, in Germany 22 % and in Poland 80 %. These countries also have a large share of publicly owned multi-apartment buildings; Sweden 30 %, Finland 38 %, and Poland 15 %. In Germany a majority of multi-apartment buildings are privately owned. Some are owned by a single person the most are owned by private companies like limited liability companies (GmbH) or stock companies (AG) 75 %. In Sweden 30 %, Finland 10 %, and in Poland 5 % privately owned. Apartments in publicly and privately owned multi-apartment buildings are rental apartment buildings (2).

The second group containing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have a much larger share of homeowned multi-apartment buildings. In Lithuania 100 % are homeowned, in Estonia 97 %, and in Latvia 76 %. In Latvia, 24 % are private and public owned.

This means that the support for energy efficiency in multi-apartment buildings must be designed differently, according to ownership. In the Baltic countries, almost all efforts need to be focused on homeowned multi-apartment buildings. Buildings owned by larger companies or public organizations are more likely to be more professionally managed, with staff specializing in building management and energy optimization, having more advanced need of support. With no multi apartment buildings owned by public organizations or private companies there are no larger building owners that paves the way for investments in energy efficiency. The RenoWave project focuses mainly on homeowned multi-apartment buildings with similar needs.

Legal ownership form for homeowned multi-apartment buildings

Similarly to the ownership of multiapartment buildings, also the legal form of homeownership varies a lot between BSR countries. There are basically three different legal forms of ownership but with important varieties.

- In association owned multi-apartment buildings (3) the building is owned by a homeowner association. Members of the association own the right to use the apartment in return for a fee. The users do not formally own the apartment, but own shares in the association.

- In co-operative-owned multi-apartment buildings (4) the building is owned by a homeowner association, but members of the association rent their apartments from the association.

- In condominiums (5), “condos”, the residents own their apartments. A homeowner association owns, sets rules, and takes care of the shared spaces. Residents are members of the association. There are also condominiums without an association (6) for shared spaces. Homeowners then share the ownership of such areas in the buildings. Rules and responsibilities for homeowners are defined in law and decisions are taken jointly in democratic ways.

In Sweden, approximately 98 % of the HOMABs are association owned, but in Finland this is unusual. Instead, 95 % of the HOMABs are condominiums with an association, not being a legal form if there is no association. Responsibilities between apartment owners and associations are pre-defined in a so-called “responsibility sharing table”, which defines who – either the association or homeowner – is responsible in certain areas, e.g. outer/inner windows or outer/inner doors. For the common spaces, the association is always responsible.

In Poland, about 40 % are association owned, 5 % co-operative owned, and 55 % condominiums with associations. In Germany and in the Baltic countries 100 % of the legal form is condominiums, with or without associations. In Germany and Estonia, all HOMABs must have an association as a legal body to be responsible for shared spaces in the building. In Latvia and Lithuania, there are no requirements for having an association. Residents own shares of common areas and functions of the building. Residents can jointly decide to contract a building management company for maintenance and different services, but it is not a legal body representing the building. In Latvia, such contracting is getting more common.

This means that there is a huge difference in the decision-making process in partner countries, as well as in practice – who decides and pays for investments in the buildings, who is actually responsible for the common spaces and functions such as roofs, facades, staircases, elevators, storerooms, laundry room, boilers, shared heating and ventilation systems, etc. It can be assumed that in Latvia and Lithuania, energy efficiency investments are a lot more challenging to implement.

Decision-making in homeowned multi-apartment buildings

Due to the difference in legal forms of ownership, the decision-making also varies between BSR countries when it comes to energy investments. In Finland, Germany, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania almost all decisions about investments need to be taken by all homeowners jointly, but it is enough when most residents favor the decision. Decisions can be made by voting at a general assembly or by signing a decision. In all the cases when a legal association exists, one can take also its own decisions, at least smaller ones. In Latvia and Lithuania, if there is a contracted building managing company assigned to a building, it can take some smaller decisions, especially if urgent emergency works are needed for the building. In Finland and Poland, there is almost always a building manager elected or contracted by the homeowners that can take some smaller decisions together with the building board, and major decisions at the annual joint meetings.

In Sweden, legally all investment decisions can be taken by the board of the association, but often larger decisions go to a general assembly for discussions and decisions. Of course, this makes the decision-making process a lot easier. The main task of a board is to maintain or increase the value of the real estate/building. In practice, many boards find it challenging since board members are not professionals in real estate matters and can be afraid of taking wrong decisions.

The contracting partner for energy investments

Due to the different legal ownership forms and decision-making processes, the actual contracting for an investment in a HOMAB varies significantly between BSR countries. In cases where there is an association, it can sign a contract. But when there is no legal association, like in Lithuania and Latvia, there are two options: whether a housing association is established and the majority gives it the mandate to sign a contract for the housing association, or there are mandated persons who represent all owners and have the mandate to sign a contract based on majority voting. The actual invoice will have to be sent separately to all residents in the building. Of course, this is an extra challenge for making investments happen and it is of extra importance to have supporting institutions that act as a middle hand between HOMABs, construction companies, and credit institutions.

Professional and national supporting associations

When it comes to professional support, it is relevant to analyze who has knowledge in energy efficiency management for different categories of HOMABs. The mapping has concluded that also this varies between the partner countries. In Finland, almost all buildings have an external contract/appointed professional building manager that has knowledge of energy efficiency, or at least can rely on a large network of experts for EE-measures. In other countries, the experts are appointed on occasions when there is a need, but some HOMABs on their own initiative contract an external expert for a longer term. Not many HOMABs have their own deeper knowledge of energy issues, so how professionals are engaged in management is of great importance for the results.

In all BSR countries, except Lithuania, there are national associations for HOMABs (7). Such national associations can offer a large variety of services and knowledge in energy efficiency, depending on the country. The relevance and importance of those associations can hardly be underestimated in supporting the professional management of HOMABs

Payment for heat and electricity

Last but not least, the project has examined and benchmarked who pays for the heat and electricity in the HOMABs. In all countries, it is the apartment user/owner that has a contract with the electricity supplier and pays according to its actual use based on separate invoices, based on real measurements (meters). In Estonia, it is also usual that the homeowner association contracts and pays for the electricity, and distributes the cost based on real measurements between the apartments. This means in practice that all users/owners of homeowned apartments have an economic incentive in saving electricity. To make investments in solar PV power more interesting, there is a need to have one central meter that distributes produced electricity to all sub-meters in apartments. In Poland, investment decisions on PV are based on the plan that the produced electricity will be sold to the grid and that income will be dedicated to a fund for renovations.

How HOMABs pay for the heat varies. In Sweden, Finland, and Latvia the HOMAB association or building management company has a contract and pays for the heat for the whole building. The cost is then distributed to homeowners based on calculations. This is also mostly the case in Estonia. In Germany and a few other countries, there are real meters for real measurements of heat in separate apartments. In Germany, it is common to have more than one heating system in the same building. Some apartments might have their own gas heater, while others are connected to district heating. In Lithuania which has no associations, homeowners have individual contracts with the heat supplier and the cost is distributed by calculations.

For heat, it is more challenging to establish economic incentives on an individual level since very few apartments pay according to their real use. At the same time, the incentive exists for the HOMAB association in the cases where the contract is signed by an association. With individual contracts and payments for heating the incentives for investing in central heating systems are not as obvious.

Summary of key findings

The examination and benchmark show a surprisingly large difference in the preconditions for energy efficiency in home-owned multi-apartment buildings. The situation in Sweden, Finland, Germany, and Poland is more similar and conditions are more supportive to facilitate energy investments. In the Baltic Countries, with no multi-apartment houses owned by public organizations or private companies, there are no larger building owners that would pave the way for investments and services in energy efficiency. Lithuania and Latvia face a special challenge, having HOMABs with no associations to organize and take responsibility for the buildings.

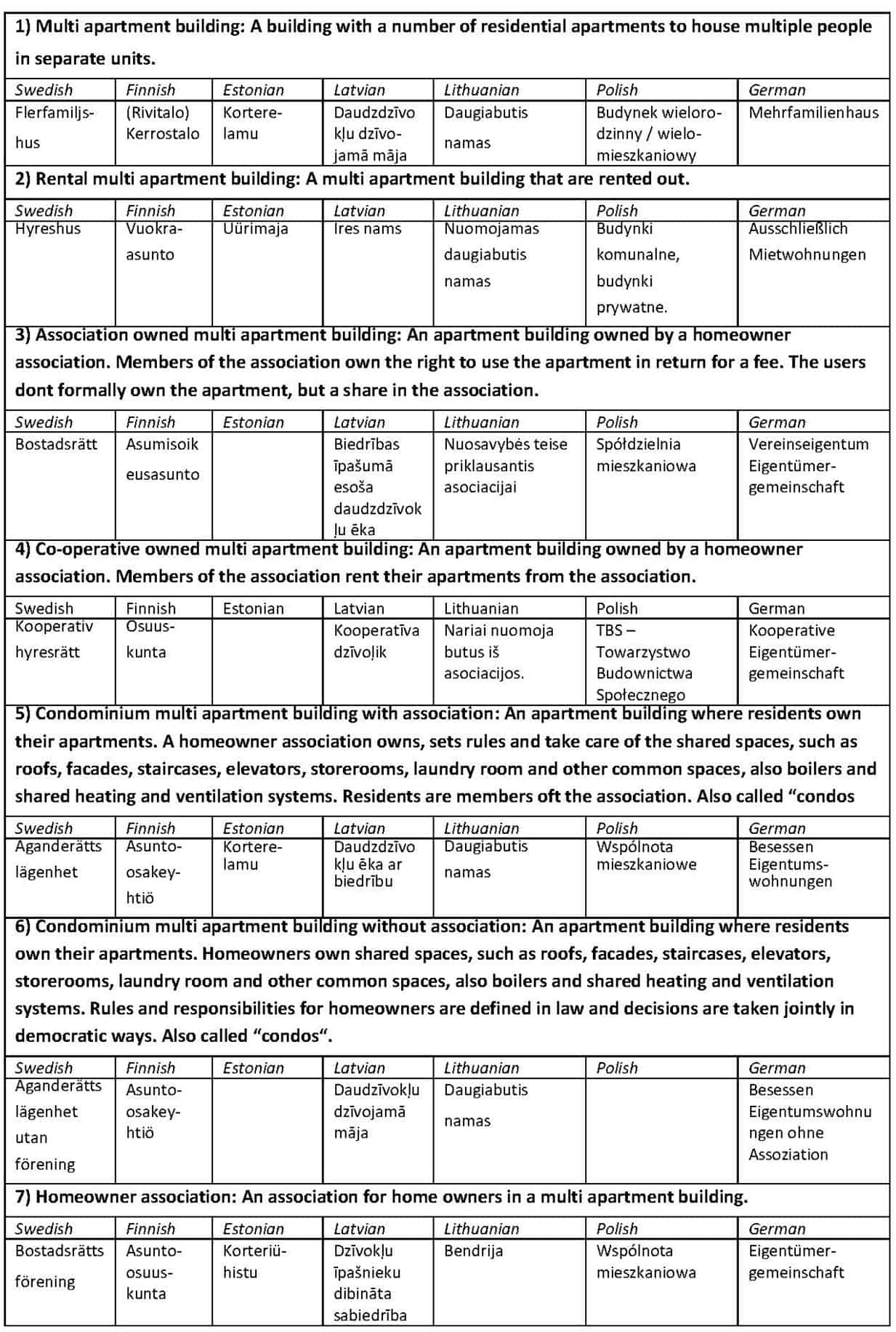

Definitions

(1) Multi apartment building: A building with a number of residential apartments to house multiple people in separate units.

(2) Rental multi apartment building: A multi apartment building that are rented out.

(3) Association owned multi apartment building: An apartment building owned by a homeowner association. Members of the association own the right to use the apartment in return for a fee. The users don’t formally own the apartment, but a share in the association.

(4) Co-operative owned multi apartment building: An apartment building owned by a homeowner association. Members of the association rent their apartments from the association.

(5) Condominium multi apartment building with association: An apartment building where residents own their apartments. A homeowner association owns, sets rules and take care of the shared spaces, such as roofs, facades, staircases, elevators, storerooms, laundry room and other common spaces, also boilers and shared heating and ventilation systems. Residents are members oft the association. Also called “condos“.

(6) Condominium multi apartment building without association: An apartment building where residents own their apartments. Homeowners own shared spaces, such as roofs, facades, staircases, elevators, storerooms, laundry room and other common spaces, also boilers and shared heating and ventilation systems. Rules and responsibilities for homeowners are defined in law and decisions are taken jointly in democratic ways. Also called “condos“.

(7) Homeowner association: An association for home owners in a multi apartment building.

Information was prepared by Marit Ragnarsson, RenoWave Project Manager, Länsstyrelsen Dalarnas län