Experiencing Supported by Nature as a PhD Student

16 April 2025

Image: Vineta Gailite in the reed-filled coastal area at Sjölax, Finland. Photo: Heli Kanerva-Lehto

From Inland Latvia to the Baltic Sea Coast

I recently moved to Hiiumaa Island in the West Estonian Archipelago Biosphere Reserve. Growing up far from the coast — in eastern Latvia, in the Daugavas Loki Nature Park — I had little direct experience with coastal ecosystems. However, I’ve always been fascinated by how pastoral farming supports biodiversity in open landscapes.

Living on a sheep farm in Hiiumaa quickly taught me how vital animal herding is for maintaining coastal meadows — and how deeply it’s rooted in local culture. I also encountered new ecological terms like coastal wetlands and coastal meadows, which differ from the floodplain systems I knew from river landscapes. To learn more, I began a junior research position at the Estonian University of Life Sciences, focusing on nutrient cycling in coastal wetlands.

Discovering Supported by Nature

I first learned about the Supported by Nature project during a research seminar. A bit of online digging led me to the Archipelago Sea Area Biosphere Reserve in Finland — home to thousands of islands. Their vast and varied coastlines offered an ideal setting to explore more about nature-based solutions (NBS), so I applied for an ERASMUS internship with Turku University of Applied Sciences.

There, I joined the Water and Environmental Engineering research group and was invited to participate in fieldwork at several learning sites. It was my first time in Finland — and I was amazed. The landscape, shaped by ongoing land uplift, revealed bedrock islands scattered among pastures and fields. It felt very different from the soft, flat terrains I knew.

Image: Vineta Gailite on a barge at Sjölax, Finland. Photo: Heli Kanerva-Lehto

Nature-Based Solutions in Action

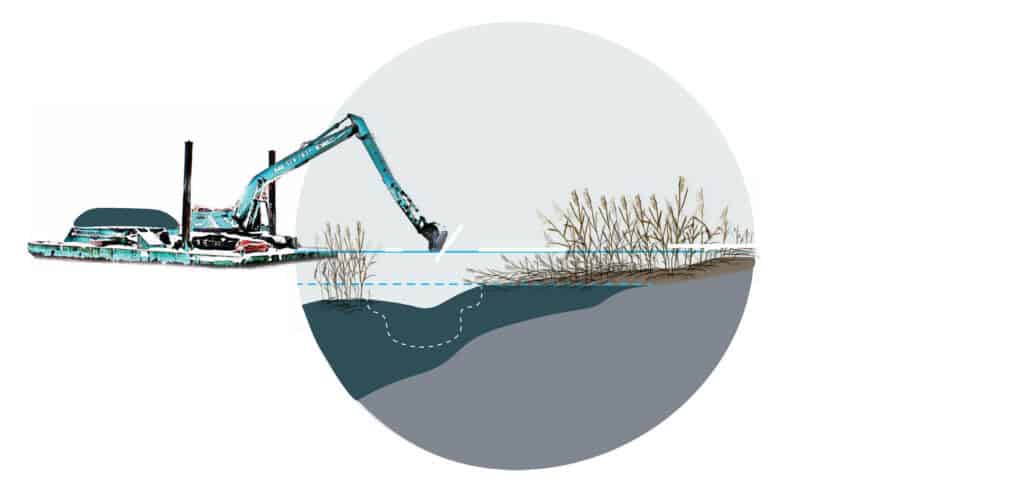

In my fieldwork, I learned how reed beds (Phragmites australis) stabilize coastlines, trap nutrients, and support biodiversity — but also how their dominance can threaten other species. Managing them through excavation and grazing becomes necessary to restore balance.

For example, excavated reed beds can create open-water habitats for pike spawning, while the nutrient-rich plant material can be reused on farmland. At other learning sites, livestock grazing is being reintroduced to increase biodiversity — a nature-based solution deeply connected to traditional land use.

Illustration: A barge-mounted excavator is used to create water pockets in a reed-dominated coastal area to enhance biodiversity and provide spawning grounds for fish. Copyright: Vineta Gailite

Illustration: A barge-mounted excavator is used to create water pockets in a reed-dominated coastal area to enhance biodiversity and provide spawning grounds for fish. Copyright: Vineta Gailite

Documenting and Sharing the Journey

Part of my internship involves documenting actions at the learning sites and creating virtual tours — using 360° images, video, soundscapes, and drawings. These tools help make nature-based solutions more accessible, especially for people who can’t visit the sites in person.

Visual communication is powerful. Drone footage, underwater clips, or “show-and-tell” moments from farmers make complex topics easier to understand — and help bridge language and cultural gaps across the Baltic Sea.

Collaboration is Key

Supported by Nature has also shown me the value of Living Labs: partnerships between local land users and researchers where we exchange knowledge and co-develop solutions. For me, this is a meaningful way to connect research with the real world.

I’m grateful to be part of this project — not just to learn, but also to contribute to something that brings together people, science, and nature.

By Vineta Gailite