Microplastic and Baltic Sea

03 December 2024

Microplastics (MPs) are acknowledged as environmental pollutants posing a risk to both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. MPs are typically defined as plastic particles ranging from 1 μm to 5 mm in size. MPs consist of a diverse mix of synthetic materials, including polypropylene, polyethene, and polystyrene. These particles can appear in various forms—fragments, fibres, pellets, granules, spheroids, flakes, or beads—characterised by high resistance to chemicals, temperature, water, and light, as well as bio-neutrality and effective oxygen/moisture barrier properties.

MPs are categorised as primary or secondary. Primary MPs are directly manufactured, often for personal care products and cosmetics, and can also arise from urban dust and the washing of synthetic fabrics. Secondary MPs result from the degradation of larger plastic items, such as plastic bags, bottles, and fishing nets, through physical, chemical, or biological processes. Both primary and secondary MPs can enter marine environments via surface runoff, wastewater discharge, aquaculture and fishing activities, airborne particles, and landfill leachate from household and industrial waste.

In households, MPs are often washed down drains and enter sewage systems. Traditional wastewater treatment plants, however, struggle to capture these particles due to their minuscule size, resulting in MPs being discharged into rivers and ultimately the ocean. Some MPs float at varying depths in seawater, while denser particles sink and accumulate on the seabed. Because of their stable chemical composition, MPs can persist in the environment for many years.

In recent years, studies have examined microplastics in marine environments to track their presence, interaction, and buildup in surface waters, sewage sludge, and sandy beaches. MPs have also been found in marine sediments and sea ice. Research shows that MPs pose a threat to sea life, as marine organisms may mistake plastic particles for food, leading to ingestion and potential food-chain transfer. MPs have been detected in the digestive tracts of fish and marine mammals and even in seafood, posing indirect risks to human health since seafood is a key part of human diets. MPs can move from the digestive tract to other parts of the body, potentially causing harm

The Baltic Sea, one of the largest brackish water systems globally, covers about 420,000 km² with an 8,000 km coastline. Surrounded by nine countries and home to about 85 million people, it has some of the highest coastal population densities in Europe [1]. The limited water exchange between the Baltic and the North Sea [2] has led it to be considered one of the most polluted seas. The Baltic Sea is highly industrialized, with heavy ship traffic and pollution from industries along its shores, including plastics production. Marine pollution from fishing and shipping, along with plastic waste, has made it one of the most affected marine ecosystems. There is an estimated 40 tons of MPs in the Baltic Sea, largely from personal care products [3]. The Baltic Sea is one of the largest brackish inland seas and water exchange is extremely slow. Therefore, microplastics will stay here possibly forever. The total input of microplastics is still increasing even though some producers in some countries have been phasing out these products.

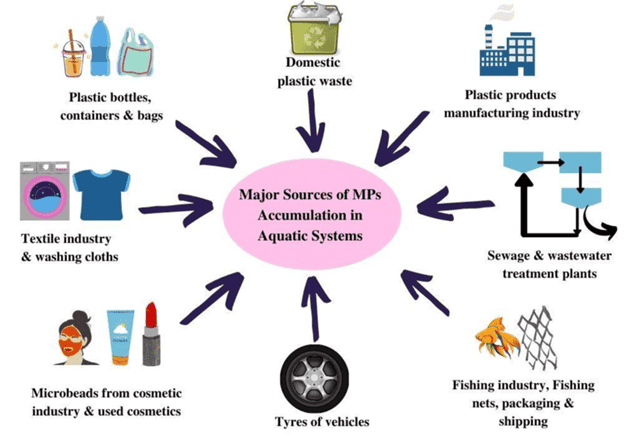

Major sources of microplastics in aquatic systems

1. Primary Sources

- Personal Care Products: Microbeads in cosmetics, toothpaste, and other products contribute directly to microplastics, as they are often too small to be filtered out by wastewater treatment plants.

- Synthetic Textiles: When synthetic fabrics like polyester, nylon, and acrylic are washed, they shed microfibers that enter wastewater systems, which can then end up in rivers, lakes, and oceans.

- Car Tire Abrasion: As car tires wear down on roads, tiny plastic particles are released, which can be carried by rainwater into aquatic systems.

- Agricultural Plastics: Plastic mulches and plastic-covered greenhouse films degrade and break down in fields, releasing microplastics that can be washed into water systems.

- Industrial Processes: Some manufacturing processes release plastic pellets, powders, or fibres, which can make their way into aquatic systems.

2. Secondary Sources

- Larger Plastic Debris: Large plastic waste such as bottles, bags, and other packaging degrades over time due to sunlight, wave action, and other environmental factors, breaking down into microplastics.

- Fishing Gear: Abandoned or discarded fishing nets, lines, and traps break down into smaller pieces over time.

- Paints and Coatings: Flaking paint from ships, buildings, and road markings often contain plastic components that gradually wear off into waterways.

- Litter and Waste Mismanagement: Improperly disposed of plastic waste that makes its way into rivers and oceans contributes to microplastic pollution as it degrades.

Microplastics have been found almost everywhere on the planet—from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains.

Here are some examples:

- Oceans and Seas: Microplastics are widely distributed throughout the world’s oceans, including remote and deep-sea areas like the Mariana Trench, where plastic particles have been found at depths exceeding 10,000 meters.

- Drinking Water: Studies show the presence of microplastics in drinking water in various countries, both in tap water and bottled water. Particles are also found in groundwater and well water.

- Air: Microplastics are present in the air we breathe, especially in large cities. These particles can be transported by wind and deposited in both urban and remote areas.

- Food: Microplastics have been found in foods, especially in seafood, salt, honey, sugar, and even beer. Fish and shellfish ingest microplastics along with their food [4].

- Arctic and Antarctic Regions: These remote areas contain microplastic particles in sea ice and snow. This indicates that microplastics are transported over long distances via the atmosphere and ocean currents [5].

- Soil and Agriculture: Microplastics accumulate in soils, particularly in intensive agricultural areas where plastic mulch and fertilizers made from recycled waste are used.

- Human Body: Research has detected microplastics in human blood, brain, lungs, and even in the placenta, raising concerns about their potential impact on health.

Microplastics pose several serious threats:

- Entering the Food Chain: Microplastics can enter the food chain through contaminated water, soil, and plants. Marine organisms like fish ingest these particles, passing them up the food chain to humans.

- Contamination of Drinking Water: Microplastics are commonly found in bottled water. These particles can carry toxic chemicals, which, when ingested, may harm human health, potentially leading to hormonal imbalances and cancer.

- Threat to Aquatic Ecosystems: Microplastics affect entire aquatic ecosystems, impacting not only the organisms that ingest them but also aquatic plants, plankton, and fish. This disruption can harm biodiversity and ecosystem stability.

- Impact on Human Health: Research shows microplastics can affect human health in various ways. Tiny particles may penetrate the intestinal wall, entering the bloodstream and potentially causing inflammation, immune issues, and other health risks. Microplastics have even been found in blood and breast milk [6].

- Persistence in the Environment: Microplastics degrade very slowly, causing them to accumulate over time. This persistence increases their negative effects on nature and human health.

Tips to reduce microplastic pollution on a personal level:

- Choose clothes made of natural materials like cotton, wool, or linen, which shed fewer microplastics than synthetic fabrics. When possible, buy fewer items made from polyester, nylon, or acrylic. If you do buy synthetic clothes, wash them less frequently or on a gentle cycle to reduce fibre shedding.

- Minimize single-use plastics by choosing reusable bags, bottles, and containers to reduce overall plastic waste.

- Attach a microfiber filter to your washing machine to capture microplastic fibres released during laundry when cleaning you clothes at home.

- Avoid products containing microbeads, such as certain exfoliating scrubs and toothpastes. Check for ingredients like polyethylene and polypropylene in personal care products and avoid these items, as they often contain microplastics. List of microplastic.

- Choose sustainable brands that focus on environmentally-friendly practices and reduce their plastic use. Here you can find a list of Zero Plastic Inside Brands.

- Follow local recycling guidelines to ensure plastics are disposed of correctly, preventing them from breaking down into microplastics in nature.

- Tire wear contributes to microplastics on roads that wash into waterways. When possible, reduce car use or consider walking, biking, or public transport.

What can be done at the municipal level or business to contribute to reducing the microplastic problem?

- Implement Filtration at Treatment Plants. Investment in filtration technologies that effectively capture microplastics in wastewater helps to reduce their entry into water bodies.

- Promote Real Eco-Friendly Solutions: Encourage citizens to use reusable items instead of single-use plastics and to choose natural fabrics over synthetic ones.

- Organize Clean-Up Events: Conduct regular clean-up activities along riverbanks, lakeshores, and in parks to decrease the amount of plastic that can break down into microplastics over time.

- Support Sustainable Businesses: Provide subsidies or tax incentives for companies that minimize plastic use, develop biodegradable alternatives, or utilize recycled materials.

- Educational Programs for the Community: Offer workshops and campaigns aimed at raising public awareness about the dangers of microplastics and ways to reduce them in daily life.

- Ban or Restrict Microplastics in Products: For instance, implement restrictions on microplastic components in cosmetics and household products.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Organize research to monitor microplastic pollution levels and assess their impact on local nature and human health. This will help in planning more effective reduction measures.

- Support Plastic Recycling Technologies: Subsidize innovations in recycling to more effectively process plastic waste, preventing it from entering the environment.

- Strict Monitoring of Industrial Emissions: Develop regulations for industrial facilities to reduce plastic and microplastic emissions into the environment, particularly into water bodies.

- Promote Alternative Materials: Support the production and use of biodegradable and eco-friendly materials instead of traditional plastics in packaging and consumer goods.

EU-Wide Ban on Microplastics

The Helcom Regional Action Plan (RAP) on marine litter prioritizes the issue of microplastics, emphasizing the need to identify various sources and engage with manufacturers and retailers. To mitigate the impact of microplastics in personal care products, Helcom recommends using substitutes to protect the marine environment.

Several states in the US have already implemented bans on microplastics in personal care products. In December 2014, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Sweden jointly called for a similar ban across the EU [7]. This proposal deserves serious consideration and support from all EU member states to showcase a collective political commitment to adhere to the EU’s precautionary principle and achieve the objectives outlined in the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD).

The European Commission has introduced Regulation (EU) 2023/2055, amending REACH to restrict microplastics. This regulation bans the manufacture and sale of synthetic, non-degradable microplastics in concentrations above 0.01% by weight, either as standalone substances or in products that release microplastics when used. The restriction applies to products like sports infill, cosmetics, detergents, and glitter, with varying transition periods based on product type. Exemptions include products with minimal microplastic release, industrial-use items, and specifically regulated sectors such as medicine and food. These measures aim to cut microplastic emissions by 70%, preventing an estimated 500,000 tons from entering the environment over 20 years.

Did you know?

- The researchers were surprised to find up to 30 times more microplastics in brain samples than in the liver and kidney [8]

- It is estimated that between 75,000 and 300,000 tons of microplastics are released each year in the European Union

- The researchers also found the amount of plastics in brain samples increased by about 50% between 2016 and 2024. This may reflect the rise in environmental plastic pollution and increased human exposure [9]

- Studies have found microplastics in human faeces, joints, livers, reproductive organs, blood, vessels and hearts.

- According to a study by the Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre (MBERC) in England, the plastic load released from clothes made of synthetic fibres (polyester, polyester-cotton and acrylic) amounts to over 700,000 large MP fibres per machine wash (per 6 kg load) [10]

- Recent studies have also indicated the presence of MPs in some terrestrial food items, such as edible fruit and vegetables and store-bought rice, but further research is needed to replicate these findings [11]

- A study of human consumption of MPs estimated the ingestion of 90,000 particles through recommended levels of water intake annually from bottled sources of water, compared to 40,000 MPs through tap water only [12]

- Microplastics have been found all over the world, from Antarctica to the Ocean, and even in clouds [13]

References

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/7604195/KS-HA-16-001-EN-N.pdf

[2] https://helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/BSEP122.pdf

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0269749122016670

[4] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9819327/

[5] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/microplastic-pollution-is-found-in-deep-sea

[6] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12403-022-00470-8?utm_source=getftr&utm_medium=getftr&utm_campaign=getftr_pilot

[7] http://www.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.232459.1433317204!/menu/standard/file/PBmicroplastENGwebb.pdf

[8] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11100893/

[9] https://theconversation.com/microplastics-are-in-our-brains-how-worried-should-i-be-237401

[10] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[11] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304389421007421?via%3Dihub

[12] https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.9b01517

[13] https://www.acs.org/pressroom/presspacs/2023/november/microplastics-found-in-clouds-could-affect-the-weather.html