Let it flow

30 June 2025

Image credit: Kalmar Municipality

“I use recycled water for irrigation” – the words are written in big letters on a tanker trailer pulled by a tractor as it bumps along through the city of Kalmar on the south-east coast of Sweden in June 2024. The trailer is on its way to a green area with newly planted trees that require special care in their first few years, especially when it gets warm and dry. Until recently, this was done according to the old practice – using ordinary drinking water from the tap, which seemed to be available in an unlimited supply. But in the hot summer months of recent years, water regularly became scarce, while the groundwater level dropped dramatically. Several water crises have hit Kalmar hard. But instead of lively discussions about new strategies and master plans, the Swedes reacted with their usual pragmatism. In various areas of local water management, both private and public, they got straight down to work and tested out alternatives. Alternatives where water is drawn from other sources in order to make it available for different uses. Is it really absolutely necessary to water urban green spaces with precious drinking water?

“The psychological hurdles are a bigger problem”

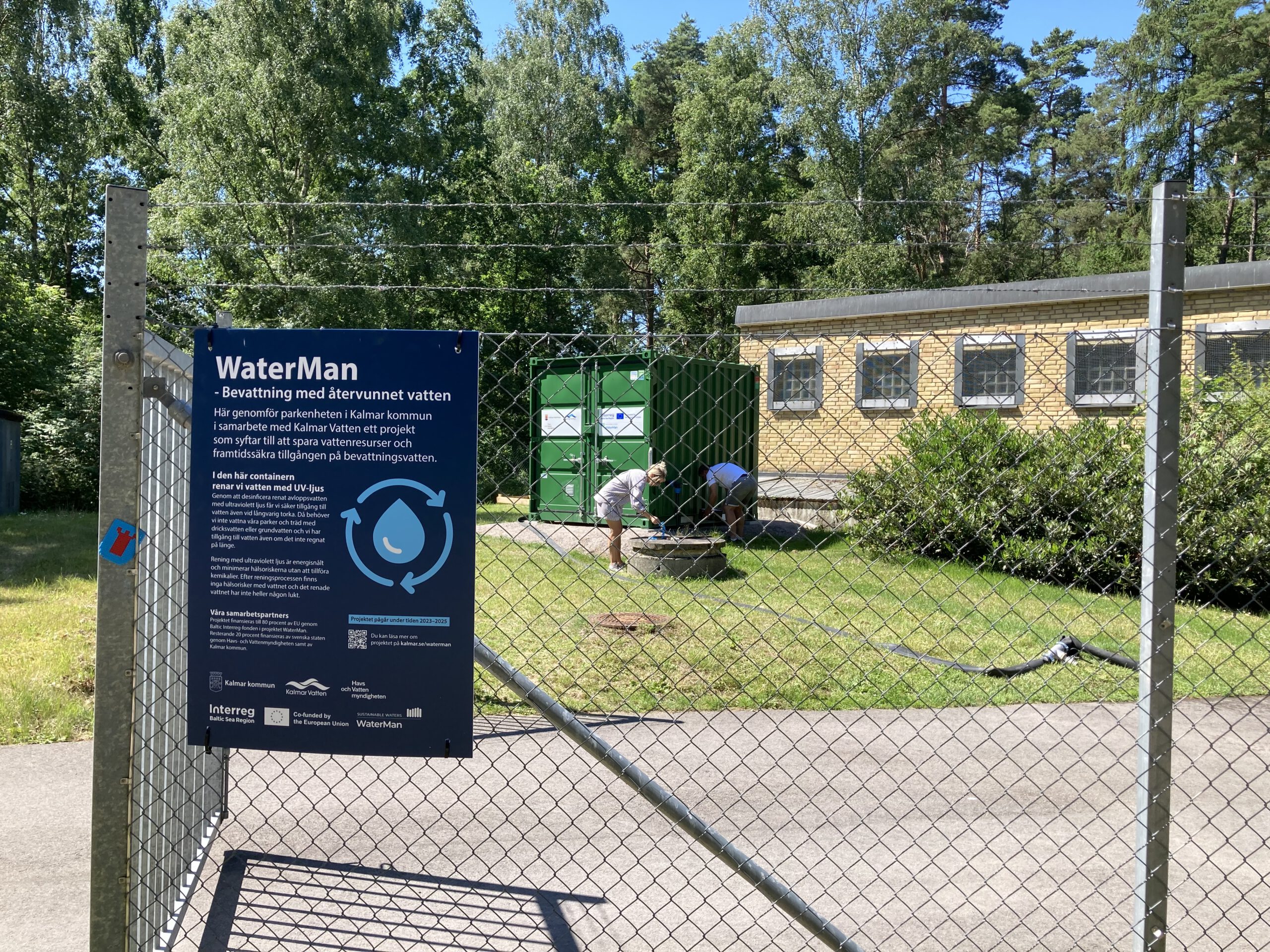

Absolutely not. It is also possible, for example, to use water from the local wastewater treatment plant disinfected with UV radiation, which significantly reduces the contamination from germs and bacteria. The Parks and Green Spaces Department is also making its contribution with this pilot project and Klas Eriksson is responsible for the implementation. He and his team purchased the components for the new system, installed them and got them up and running. “It had its technical pitfalls, but everything was doable. The necessary components were all readily available, we just had to put them together in a way that made sense,” he says. A small pumping and recycling station is now located on a canal through which the treated wastewater from the Kalmar wastewater treatment plant is channeled into the sea and back into the large natural water cycle.

Image credit: Kalmar Municipality

This station takes some of the treated water, exposes it to UV disinfection and then fills the tanker – and off it goes into the parks and green spaces. They are watered directly from the tank using a hose system. The system has been in use since June 2024 and put simply: it works. Plus, the nutritions still in the water are perfect for fertilising the soil.

Water that could also be used to water lettuce and strawberries

“The psychological hurdles are a bigger problem,” says Eriksson. “People still have to get used to the idea of using treated wastewater and other quality levels of water in their everyday lives.” Hence the prominent slogan on the tanker trailer. The aim in Kalmar is also to familiarise the public with the fact that they will no longer be able to use precious drinking water obtained from groundwater everywhere and all the time. However, Eriksson first had to do a lot of convincing at his office, among his colleagues from the gardening department, who will be working with the system every day. “There were some critical voices as to whether the handling of treated wastewater was hazardous to health,” he reports. Some resistance was to be expected, however, which is why Eriksson had taken precautions: he had work place safety experts in to draw up scientifically founded reports. He informed his colleagues in detail about the results during training sessions – “harmless” – and took the opportunity to invite representatives of the company that cleans the sewers in Kalmar. “They are working with wastewater treatment plant water that is not even disinfected. And there haven’t been any problems there either.” He could also reassure his employees that thanks to the UV disinfection the water achieves even quality level A, suitable for irrigating food crops such as lettuce and strawberries in accordance with the EU Water Reuse Regulation 2020/741.

“The various players need to communicate even better and take note of each other’s activities”

The employees’ skepticism has noticeably decreased, particularly after the first practical experiences with the system. The principle seems to be proving its worth in Kalmar simply by just getting started and carrying out testing in different areas – on a smaller as well as a larger scale. The municipal water company Kalmar Vatten AB is currently building a brand-new water recycling plant in the city that opens in 2027, which may even be producing drinking water from wastewater on a large scale. The utilisation and harvesting of rainwater are one of the key points to consider in all land development projects. The sports department recently tested whether it could use rainwater from retention ponds to water football pitches. And much more besides. The joy of experimentation and the spirit of optimism in various areas does not mean, however, that these new water activities are completely uncoordinated.

Hanna Berggren / Kalmar Municipality

Hanna Berggren is responsible for ensuring that these projects and activities work together as well as possible. “I was hired to manage Kalmar Municipality’s new comprehensive water strategy, and I had a lot to learn myself,” she explains. “One of the most important things I learnt was that the various stakeholders and departments needed to communicate much better and take note of each other’s efforts to recycle more water in the first place.”

Creating a coherent overall picture and then putting it into practice

In the meantime, a lot has been achieved in this field too. For example, the experts of Kalmar Vatten AB provided Eriksson and his team with advice and support when it came to commissioning the UV disinfection system. The company is also very interested in the experience gained from the mobile system. They are considering using something similar at a later date to disinfect water in the new large-scale plant. Nevertheless, much remains to be done for Berggren. In the medium to long term, she must draw up a coherent overall picture of what quantities of water will be needed in the future, in what kind of quality and for which applications – and she must work towards making this a reality.

“What makes economic sense depends on the individual local setting”

S

Image credit: Kalmar Municipality

ometimes there are still small problems: “The department of Parks where Klas Eriksson works should contact the sports office again and offer to work with the mobile system.” Meanwhile, it has become apparent that the rainwater retention ponds from which the football pitch is to be watered sometimes almost dry out in the hot summer months. According to Berggren, larger infrastructure measures may also be involved: “There are also plans here in Kalmar to use treated grey water – i.e. slightly contaminated wastewater that is free of faeces – for flushing toilets in the future.” In order to realise this across the board, completely new pipelines would be needed. This is still a long way off, but a dual-pipe system has already been installed in a pilot building at the Kalmar hospital. A feasibility study is currently investigating how this can best be utilised and perhaps even connected to the new water recycling plant.

In principle, a completely new attitude to water is required in this region

Added to this are the valuable suggestions that both Berggren and Eriksson receive as representatives of the municipality of Kalmar in the “WaterMan” project’s peer-learning programme. In this Interreg project, representatives from various countries bordering the Baltic Sea are exchanging ideas on new water strategies that suit the region’s specific circumstances in light of the noticeable effects of climate change. In Braniewo in Poland, for example, they are considering recycling water from swimming pools.

In Klaipeda, they are building new retention ponds because there is now much more water to collect due to increased heavy rainfall events – also as a result of climate change – which can then be put to good use during periods of drought. Something similar is currently happening in Västervik, Sweden, where they are watering sports fields and cemeteries, for example, with the help of new “multidams”. “Our UV technology could also be used for collected rainwater,” explains Eriksson. “But if you have to build such basins from scratch, it could also be cheaper to disinfect sewage treatment plant water.” It always depends on the individual local setting as to what makes economic sense.

Image credit: Kalmar Municipality

As well as the big picture, there are still many details to be worked out. According to Berggren, this is currently taking shape as part of WaterMan. “We will also have to understand water as a valuable resource around the Baltic Sea in the future.” This includes accepting different qualities of water for different uses and tapping into other sources of “usable water” besides groundwater. In principle, a completely new attitude to water is required in this region, where there has always been an abundance of water. Nobody will have to suffer from thirst, but perhaps they will have to say goodbye to a few cherished habits, such as watering their own private garden with drinking water. There are alternatives and they are already working in practice. That’s the good news that is coming out of Kalmar right now.

(Text status: 31 July 2024)

Would you like to see how the water recycling measures in Kalmar have progressed and experience the final results on site? Register for the WaterMan Final Conference & ERB Water Forum in Kalmar & Västervik / Sweden on 25–26 Nov 2026.