A turning point in water management

30 April 2025

The Kalmar region hasn’t voluntarily become a pioneer of a new water management approach in the Baltic Sea Region. It all began in 2015, when it was so dry for weeks on end on the south-east coast of Sweden that some farmers had to slaughter their livestock. They had run out of feed for the animals. Then, in the summer of 2018, temperatures once again reached record levels. The municipal water company could not satisfy the entire demand anymore, and decided to prioritize households over industry. The company Xylem, which operates a large production facility for – ironically – water pumps in Emmaboda just outside Kalmar, was less than a week away from disaster. Every day of shutdown due to a lack of process water would have caused financial damage totalling multiple millions of Swedish krona. Several hectares of coniferous forest were already on fire when the long-awaited rain finally came. During roughly the same period, the water shortage on the holiday island of Öland was so severe and sustained that the construction of a new seawater desalination plant to supply the island with drinking water became inevitable. But desalination is energy-intensive and the high quality of the end product does not make sense for all uses. Do we really want to continue watering green spaces and supplying industrial plants with precious drinking water? As the groundwater level in the Kalmar region sank, awareness of the problem grew and old ways of thinking broke down – due to climate change.

The core issue is rethinking water cycles

Tobias Facchini

Region Kalmar County is now the Lead Partner of the transnational Interreg Baltic Sea Region project WaterMan, which is campaigning for new water management in the area. Seven regions from six countries come together regularly in a group of around 30 people for “peer learning” and to develop innovative strategies together. Naturally, the Swedes in particular had a lot to say to the others: that they no longer want to access precious groundwater for all uses in future. That they want to test systems which purify water from retention basins and wastewater treatment plants for irrigation purposes. And that they are planning to try out various approaches on a small scale that should also be used on a larger scale in a new water recycling plant in the city of Kalmar from 2027.

Crisis is the mother of invention and Kalmar had already been hit particularly hard. Nevertheless, the flow of information between the coasts of the Baltic Sea was reciprocal from the outset. Tobias Facchini, water expert at Region Kalmar County, remembers the initial phase of project development: “2018 was also a crisis year for the other regions, so in 2020 there was at least agreement on the basic direction – climate change will force us all to rethink our use of water in one way or another.” And elsewhere, according to Facchini, there were already concrete ideas for pilot projects, for example in Braniewo, Poland, which wants to recycle water from a public swimming pool.

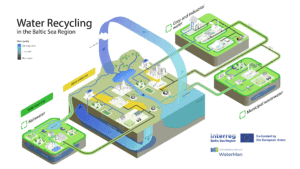

This rethinking of water cycles is the core of WaterMan today, explains project manager Jens Masuch from the German company GA-MA Consulting. He is coordinating the peer learning. “In the past,” says Masuch, “people in the Baltic Sea Region mainly used groundwater, treated the wastewater afterwards and channeled it back into the large cycle via the rivers – until it was available again as groundwater in a naturally purified form after some time.” However, the crises of recent years have clearly shown that it isn’t possible to continue in this way. “WaterMan’s objective is therefore to incorporate new smaller cycles into the large water cycle in the future, in order to tap into other sources of usable water, for example rainwater or water from wastewater treatment plants. “It’s literally about recycling water in order to make it usable again more quickly,” says Masuch. Low-threshold solutions are now being sought for this. And in addition to drinking water, other quality levels for differ ent applications will have to be accepted.

ent applications will have to be accepted.

However, these are insights that were not immediately plausible for everyone involved in the project. “We have travelled on a long journey together,” says Masuch, who studied geography, alluding to the numerous meetings and video conferences during the project’s development, which initially involved a lot of discussion about the subject focus. This was because many of the regions saw a more pressing and more visible problem resulting from climate change: extreme rainfall and flooding. Initially, they were more concerned about too much water rather than too little. Above all, they wanted to talk about the construction of retention basins and the renaturalisation of landscapes whose water storage capacity had been lost in recent decades in favour of agricultural efficiency.

A drought crisis experience – water recognised as a resource

Basically, it was only a small step from there to thinking about all of this together in a meaningful way. And once again, it was a specific crisis that provided the decisive impetus. “The other regions were soon not just confronted with an increase in heavy rainfall events, they were also experiencing more dry periods, as we did in Kalmar,” says Facchini. And Masuch adds: “Suddenly there was this ‘aha’ moment – this storm water has a value; we have to utilise it! The catchment basins are a buffer for floods, but they can also be a reservoir for the next drought.” In other words, what all those involved in the project suddenly realised when they looked at the situation together was nothing less than a completely new approach to water management, tailored to the specific situation of the Baltic Sea countries in the time of climate change. An approach that must find an intelligent balance between the chaotic alternation of too much and too little water.

Jens Masuch

A closer look at the EU’s Water Reuse Directive confirmed what the consortium had already suspected. This topic has so far rather been considered in Europe from the perspective of semi-arid, i.e. dry, climate zones in the south. The regulations mainly refer to the reuse of water from wastewater treatment plants. But that method can only be one of several options in the north, which is still very humid overall. There are also a large number of other sources to be opened up and taken into account, which can be tapped in dry periods or specifically created for periods of drought. And this raises further challenges and questions in addition to the cost-benefit analysis in individual cases. For example, how should a rentention pond be constructed and, above all, where should it be located so that the retained rain or storm water can be used directly?“ After this broadening of perspective, it suddenly seemed relevant to all the regions we were in dialogue with to understand water as a resource and to deal with these questions” recalls Facchini.

The name “WaterMan” says it all: water must be well-managed in future. The project consortium is building up a wealth of experience from which others will also benefit. It is to be expected that even more regions around the Baltic Sea will soon want and need to take a more strategic approach to the issue, because they are experiencing more and more phases in which their water requirements exceeds local supply. There will be a toolbox to help them find answers to the two central questions: What sources other than groundwater can we use? And what quality levels, other than drinking water, are suitable for which applications in our location? But there are also regulatory problems to solve. In Sweden, for example, the law does not yet allow water companies to offer different prices for different water qualities. And last but not least, it is also a question of gaining public acceptance. Not everyone is comfortable with the idea of giving up cherished habits such as watering their own garden with drinking water – as the experiences of the crisis summers in the Kalmar region have also shown. That means, in times of crisis fatigue, that there will also be a communication challenge, which WaterMan has taken into account.

Even if the Baltic Sea Region has to find its own way towards future-proof water management, it is worth taking a look at areas that have for a long time been struggling with water scarcity. This was demonstrated by a joint study trip to Murcia in Spain in spring 2024. “This region has increased the recycling of wastewater from zero to 98 per cent within 20 years,” explains Masuch. “It has become commonplace to use this water in vegetable cultivation.” The Baltic Sea Region can learn from this experience, and solutions developed there can be adapted here.

Whether in Murcia, Kalmar or on the other coasts of the Baltic Sea, people learn from crises. But they also learn from each other. WaterMan ensures that progress is made as quickly as climate change requires us to in the Baltic Sea Region.